Blogger Ron Cat died peacefully in his sleep October 2, 2020, after 18 wonderful years with us. Bob, Nina, and I miss him.

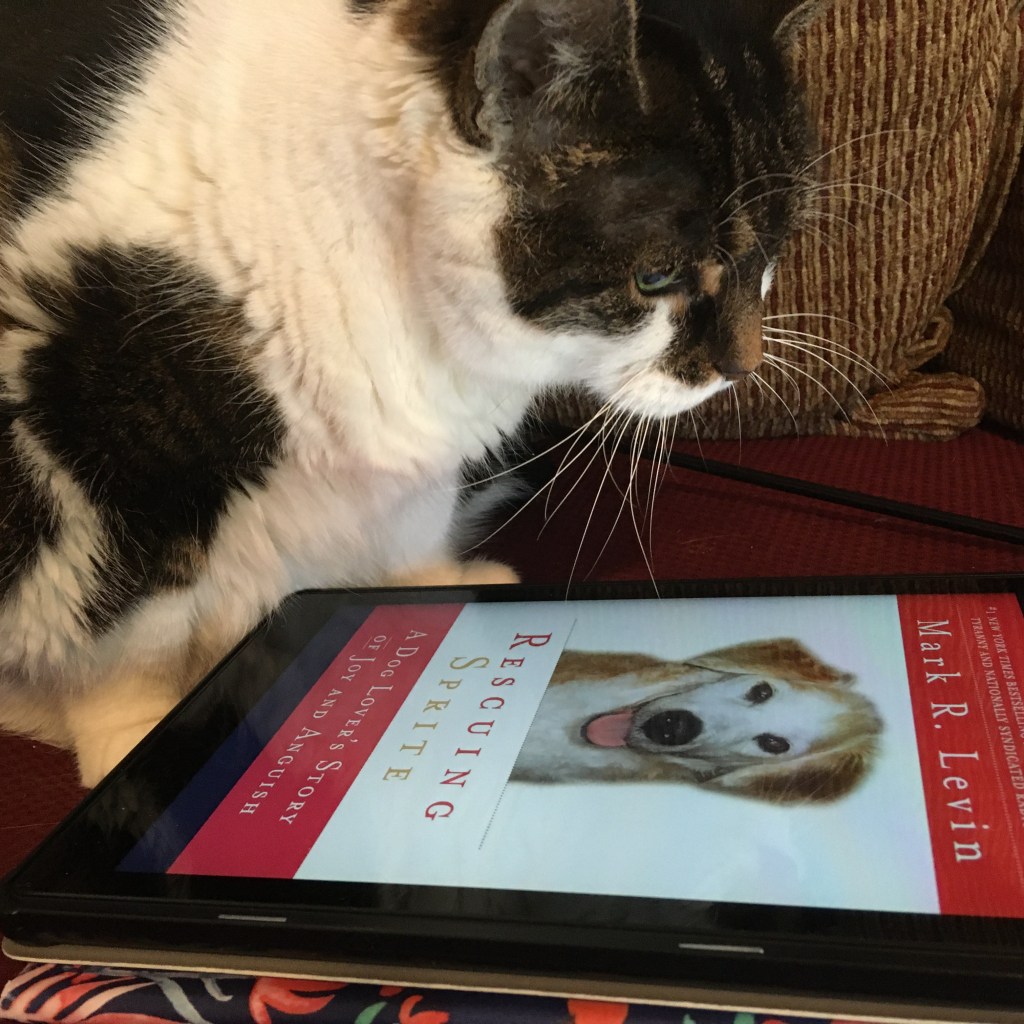

Nina seems perplexed by Ron’s absence. She sniffs around his favorite chair, hides in different parts of the house, and demands affection—she’s typically aloof. She found a little solace reading Rescuing Sprite: A Dog Lover’s Story of Joy and Anguish by Mark L. Levin. It’s a tearjerker that details the emotions behind the death of a dog. As Levin aptly wrote, “Goldfish, turtles, and hamsters are pets. Dogs are family.” So, she insists, are cats!

Ron’s birth into a feral cat colony in our backyard prompted us to get involved with a TNR (trap, neuter, return) program. As with many issues, we didn’t get involved until the problem landed literally in our backyard. At the time, the Lakeview neighborhood of New Orleans had an out-of-control feral cat problem. According to the Feral Cat Project, 75% of feral kittens die or disappear by six months of age. They risk being hit by cars, injured by other cats, attacked by predators, or developing diseases. These factors lead to an average lifespan of three years. Thousands of others are euthanized in animal shelters every year. The most humane and effective way to control feral cat populations is through TNR. Controlling their ability to reproduce decreases the population and prevents disease from spreading.

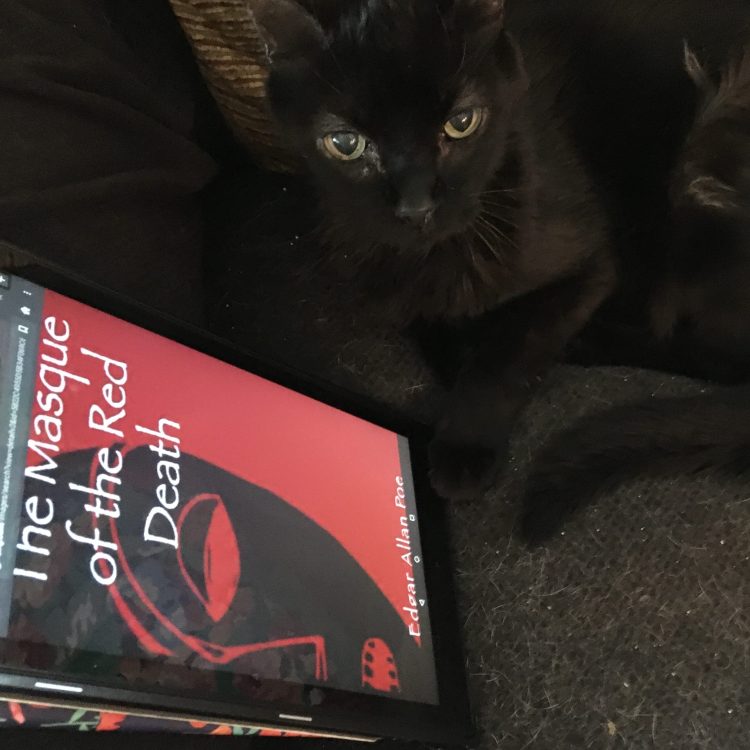

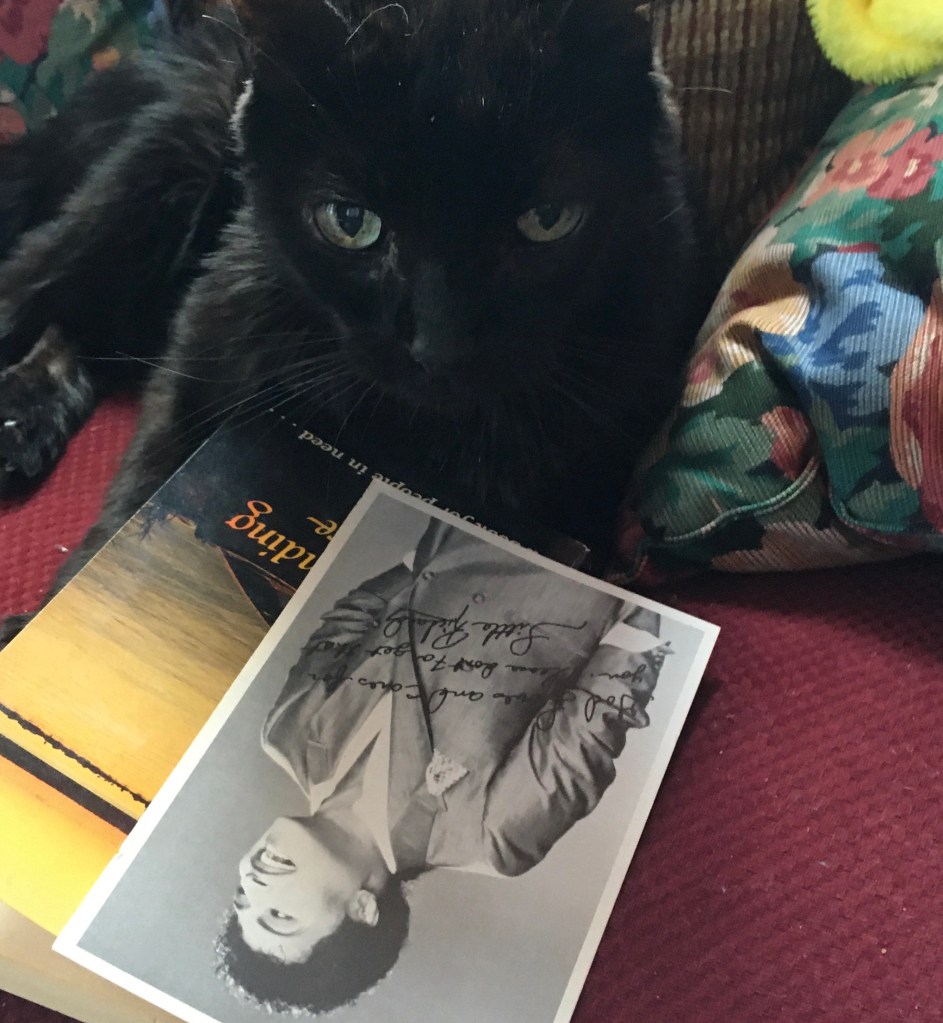

Although we fed the ferals in our colony, Ron waited on our doorstep every day for his favorite treat—a piece of turkey. On a particularly cold evening in January 2003, he slipped indoors and stayed hidden for three days. Just when Bob thought that Ron had succumbed to life on the streets, he poked his little black head out from under a bookcase. “I guess we now have a cat,” Bob proclaimed as we headed to a local pet superstore for supplies. That was January 26, 2003. Football fans may remember the date as Super Bowl XXXVIII, when the Tampa Bay Buccaneers handily beat the Oakland Raiders 48-21. Or that during the halftime show, Shania Twain belted out, “Man! I Feel Like a Woman,” Gwen Stefani ad-libbed “I’m just a girl (at the Super Bowl),” and Sting delivered his “Message in a Bottle.” But we remember it as the first time we came home to our first pet.

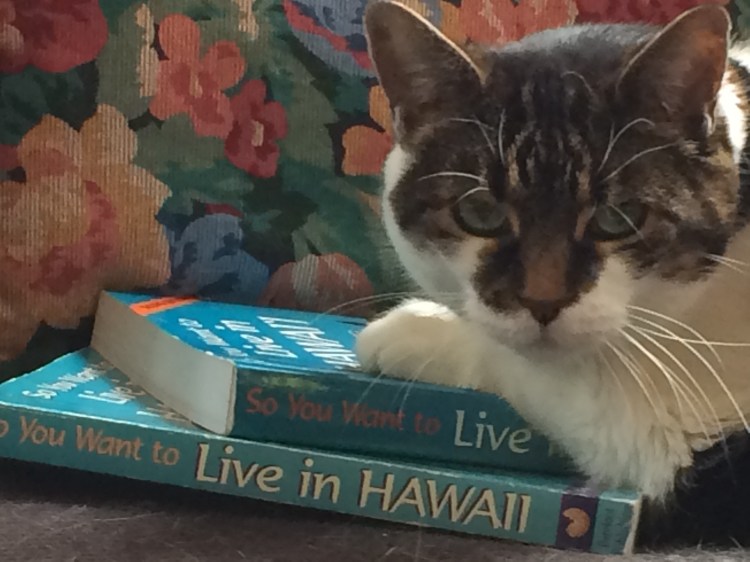

We went on to rescue a dozen or so other cats, but about a year later, Nino and Nina knew a good deal and adopted us, too.

The five of us became a traveling road show. Together, we evacuated New Orleans in advance of Katrina, landing first in Mandeville, about 30 miles north of Lakeview, then Houston, six hours west. After three weeks, we found an apartment in Baton Rouge. Eight months later, we moved to Fairfax, Virginia. Our three feline companions flew as live cargo, even changing planes in Texas. Three months ago, Ron and Nina flew with us as carry-on baggage when we moved to Southwest Florida.

Nino died 8 years ago from cancer. Following that trauma, we doubled our healthy cat visits with our vets at Merrifield Animal Hospital to twice yearly. We caught several of Ron’s medical conditions early: feline odontoclastic resorptive lesion (FORL), subcapsular perinephric pseudocysts, kidney stones, kidney disease, heart murmur, high blood pressure, recurring nasal infections, and chronic constipation. When you add in his initial rescue and five moves, he far surpassed the legendary nine lives—all made possible by Bob’s love.

There’s a popular bumper sticker out there with a paw print that reads, “Who rescued who?” (That grates on the English teacher and editor in me, who always corrects the second pronoun to whom.) Ron rescued us. More specifically, he rescued Bob.

They were buddies. Ron tolerated me, since I provided food and medicine. But Bob was his main squeeze. He sat on no one else’s lap. In his pre-Katrina days, Ron would wait on the doorstep. Post-Katrina, it was in the hallway. Bad days at the office melted away. Anxieties disappeared. Stormy weather faded into sunshine. Retirement meant instant gratification. They had rescued each other.

We miss him.