Bucket lists. You know, the silly name for things to do before we kick the bucket.

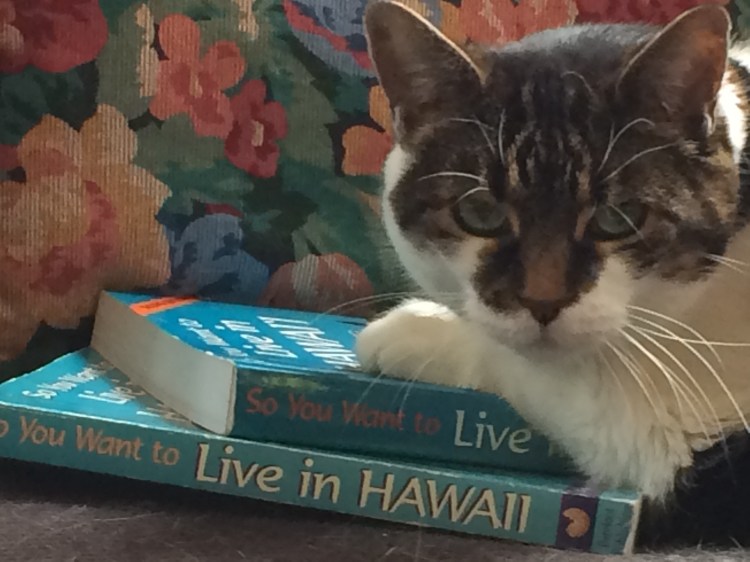

You can read about them, as my friend Kathleen’s cat Lollipop is doing; check them off a list, as Kathleen and I recently did on our adventures in Alaska; or count the blessings of accomplishing a goal. That’s where magic happens.

Yes, I danced with the goddess Aurora, trailing her borealis beneath a gazillion stars; mushed through a midnight forest aglitter with hoarfrost; and bathed in hot mineral waters that gushed from ice-bound rocks.

But I also met everyday people in and around Fairbanks, who were checking off their own bucket-list items. I began to notice that achievement is often a beginning, not an end. It triggers an honest smile and a humble confidence that can affect others’ lives.

Take, for example, Michi Konno. Born and raised in Japan, he moved to Alaska in 1999 to mush dogs. After checking off his goal to compete in the grueling Iditarod, he now opens his home to aurora seekers to share with them the enchantment of the night sky when it comes to life.

Kathleen and I met him when he fetched us—and 10 other seekers—at our downtown hotels at 9:30 p.m. and drove us 35 miles to his remote A-frame with a 360-degree view of the Alaska Mountain Range. At least that’s what he claimed. All I could see from the frigid deck of his warm abode was a moonless, obsidian sky generously sprinkled with countless stars.

“There,” a fellow trekker cried, jabbing a mittened finger northward. “Below the Big Dipper. Can’t you see it?” I couldn’t. “Use your phone. It can pick up what your eyes can’t.”

I wanted more than the illusion of light recorded through the lens of my phone’s camera, but I followed his advice. Sure enough, the phone captured a pale green streak over the horizon.

“Okay, God,” I prayed into the midnight grandeur. “If this is what I was meant to see, I am grateful. But an astral wisp was not what I had in mind.”

“Be patient,” God whispered through Michi’s soft voice.

Michi knows that patience is hard, especially when awaiting a bucket-list experience. So he offered his guests cocoa, cookies, and chocolate. Then, as if to illustrate that elusive yet discernible confidence that can transform lives, the former musher sat back and played a documentary on the Iditarod, which had just commenced in Anchorage, hundreds of miles to our south.

I’d heard about the brutal thousand-mile, multi-day race that showcases the athleticism of Alaska sled dogs while commemorating the 1925 dash to transport lifesaving diphtheria drugs from Anchorage to Nome by dogsled.

All very interesting, I thought, as I paced between the warmth of Michi’s lodge and the frigid outdoor deck. But I wanted Aurora—the phenomenon that results when charged particles from the sun collide with Earth’s atmosphere, the magic that ancient cultures feared, my reason for being here.

Then, shortly after 1 a.m., Michi shattered the frozen ennui with a booming voice that sounded like a musher spurring his sled dogs into action.

“Now!” We jumped to our feet like sled dogs. “Everyone. Out back. Now. Now.”

Before our wonderous eyes, the lazy green streak began to pulsate, then dance. Like smoke breathing through the sky, Aurora swooshed then bloomed like a feathered plume up to the zenith. For nearly an hour, she consumed the boundless sky swaying and shifting this way and that.

It’s one thing to understand the science, or to conjure the myths. It’s another to stand in wonder beneath a roiling green maelstrom tinged with purple, yet neither feeling nor hearing wind. I pocketed my camera and absorbed Aurora’s magnificence. Pictures, even videos, are inadequate. It was impossible to document.

So was dashing through the snow in an eight-dog-open sleigh, two nights later, again commencing at 9:30. (Magic, you know, happens mostly at night.) Our guide was another bucket lister. Like Michi, Ron came from elsewhere—Pittsburgh—to run the Iditarod.

Dog mushing, we learned, is not only Alaska’s official sport, but also its obsession. And race fever is contagious. Through osmosis, we learned the names of the top contenders, the scandals that plagued them, and their dogs’ lineage.

Who knew, for example, that Brent Sass would finally win after six losses? Or that he would beat Dallas Seavey by more than an hour, depriving the third-generation musher of a record-breaking sixth title? Or that Dallas’s father, Mitch, would poorly strategize his finish, coming in at a distant 16th? Behind Michelle Phillips, no less (the 52-year-old musher, not the 77-year-old singer), who placed 11th.

For our midnight run, Ron selected 8 of his 20 prized Alaskan huskies. Unlike the stereotypical sled dogs associated with fluffy fur, blue eyes, and curly tails, Alaskan huskies are pedigreed mutts, if you will, with lineages that include huskies, hounds, setters, spaniels, shepherds, retrievers, border collies, and, of course, wolves. They are well-conditioned athletes who can burn 10,000 high-quality calories a day; their training is overseen by specialized veterinarians; and they are bred for speed, tough feet, endurance, and an unbridled love to run.

In fact, when Ron hooked his team to their gang lines, they yelped and howled in excited anticipation. So, I joined in. At which point, they all abruptly stopped, as if to ask, “WTF?” After a moment of silence, they resumed, as did I. I’ve never seen such happy dogs.

Atticus and CiCi were the lead dogs that night. Leads must be intelligent to sense the trail, follow commands, and set the pace. Behind them, swing- or team- dogs maintain speed and help with corners. Wheel-dogs, generally the strongest, are positioned closest to the sled.

“Ready?” Ron asked us, as he flicked on a powerful lamp clamped to his head. We were. “Hike!” he commanded his team. And with that, we bolted into the arboreal forest aglitter with what looked like millions of diamonds spilling like fairy dust amidst branches of spruce and willow. A golden crescent moon waxed on the horizon.

And when he switched off his headlamp in search of the northern lights, we hurled through utter darkness at 10 m.p.h. in zero-degree air. Flying among the stars was pure magic.

Ron steered the gleeful dogs with Gee (right) and Haw (left). As they raced nonstop, they licked snowbanks to cool themselves off. Kathleen and I, on the other hand, were cold. Although we had layered our clothing appropriately and stuffed mittens and boots with warmers, the ride was bone-chilling.

So, when we arrived an hour later on Chena Lake, we rushed into a warm ice-fishing hut to crowd the fire and drink cocoa. Our companions, a family from Minnesota, were catching chinook salmon for their bucket-list adventure.

Once thawed, we all took turns watching and photographing Aurora as she brushed the horizon with delicate neon strokes.

After a couple of hours, Kathleen and I bundled ourselves back on the sled for another frigid ride. We slept like dogs that night, dreaming of our magical mystery tour.

Our third tour guide, Aaron, led 20 of us—polar pilgrims, if you will—on an 18-hour trek from Fairbanks to the Arctic Circle and back along the Dalton Highway. He also was a bucket-list achiever with an Iditarod story of his own.

A grad student at the University of Alaska studying rural economics, Aaron had been a photographer in Los Angeles when he gave it all up to live in a dry cabin (i.e., one with no water) to work with a kennel of sled dogs. He was, in fact, scheduled to photograph the Iditarod—another item on his own bucket list—when the opportunity fell through. But exuding the humility wrought by achievement, he was content to drive a tour bus.

It was really a diesel truck equipped with CB radio, satellite telephone, safety kit, and spare tires.

The Dalton Highway is the road that built and now services the upper half of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline. Many people are familiar with it from the History Channel series Ice Road Truckers. Not a road for the meek, it’s a 414-mile stretch of gravel and dirt with steep grades. It runs from north of Fairbanks through the wilderness of the Brooks Range to the Prudhoe Bay Oil Field on the shores of the Arctic Ocean.

Our tour went as far as the Arctic Circle, which is about the halfway point on the highway. It marks the northernmost point at which the sun is visible on the December solstice and the southernmost point at which the midnight sun is visible on the June solstice. Crossing it was on Kathleen’s bucket list.

Aaron’s nearly non-stop narration was full of history (the 800-mile pipeline was built in two years); engineering (the pipeline supports accommodate 170-degree temperature variations as well as seismic vibrations from earthquakes); geography (the Yukon River is the fifth largest river in the world, based on water volume); botany (black spruce is one of only a few trees that can grow over permafrost); culture (some ancient myths say the aurora borealis is the gods playing ball with the head of a walrus—or walruses playing ball with the head of a human); and recipes (to cook moose, marinate it first in soy sauce, olive oil, Worcestershire sauce, lemon juice, and spices, then sauté in butter).

We passed through Joy (population 2), which now serves as a rest station, complete with “dry” facilities, i.e., outhouses. We stopped for pictures at the Enchanted Forest, Yukon River, and the iconic Arctic Circle sign. One young man on our tour was a doctoral student who gathered some permafrost for his bucket. At the Yukon River Camp, I met a middle-aged woman who had driven from her home on the east coast of Florida to fulfill her own bucket-list dream to work in the Alaskan wilderness. On the way home, we searched for Aurora. But I think she may have been tired. We sure were.

Not all of our adventures were cold. Or involved stories of the Iditarod

Two artists at the UA Museum of the North were bucket-listers who warmed my heart. Michio Hoshino (1952–1996), was a Japanese-born nature photographer who fell in love with Alaska as a high-school student on vacation. A renowned wildlife photographer, he was killed by a brown bear while on assignment. Claire Fejes (1920–1998) moved from the Bronx to Fairbanks in 1946 to paint self-portraits, neighbors, and landscapes. After a stint in an Inupiat whaling camp, she mounted a one-woman show back in New York.

Chena Hot Springs was hot. Like 150 degrees hot—the temperature of the water when it steams from snow-covered rocks—and cooled to an average of 106 degrees for bathing purposes.

And far from hot, the Castner Glacier ice cave was definitely cool. So was getting there. It’s an easy 144-mile drive from Fairbanks on the Richardson Highway. The Alaska Range soared to the west, with Denali anchoring its southernmost reach and contrails spun like silk threads by Air Force pilots conducting training exercises.

The crystal-blue day attracted all kinds of day-hikers—families, dogwalkers, military troops—to the level, mile-long, hard-packed snow trail. Yet it wasn’t crowded. We greeted each other with smiles, like fellow travelers upon a mystical labyrinth. When I inadvertently stepped into a hip-deep snowdrift, a couple of young men hoisted me back onto the trail.

“I used to be an accomplished hiker,” I said, humility kicking in as I brushed snow off my leg.

“And I’m becoming one,” the one named Sean replied. He asked if he could walk with me.

“Ah, so you can help an old lady across the street,” I joked.

“No. Just across a glacier.”

A few hundred yards later, we arrived at a blue-ice cave of Castner Glacier. Its walls were like a giant uncut aquamarine—both Kathleen’s and my birthstone. Gold-like sediment threaded through its facets.

I have my photographs—and plenty of them. But the memory of that giant jewel is a souvenir I now wear close to my heart. It reminds me that in traveling from the top of the world to the depths of my soul, I had stumbled—quite literally—upon a humble confidence that holds transformative power.

I had learned to share the wonder of aspirations. And the joy of achieving them. They weren’t all things. Some were as simple as a smile, as complex as patience, or as practical as a helping hand.

That’s what makes bucket lists so magical.