When your cat is diagnosed with a chronic health problem, you are often faced with the daunting process of balancing state-of-the art medical options with quality-of-life preferences. My journey into the world of specialized veterinary care began with a single step. A semi-annual well-kitty visit revealed that Ron, a 14-year-old black cat, had a cyst on his right kidney.

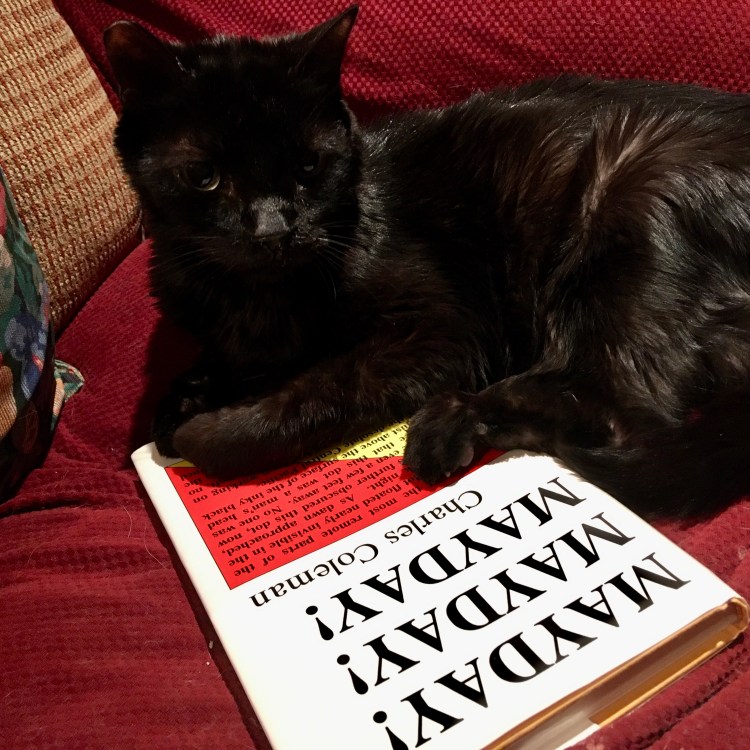

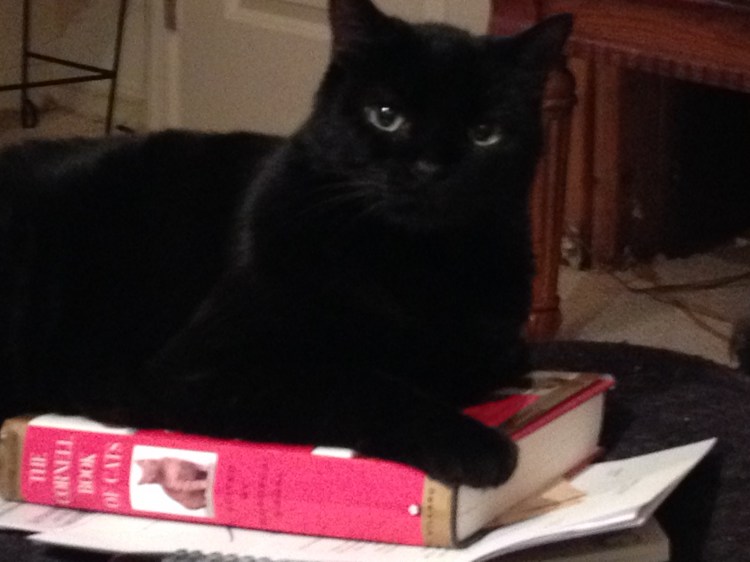

Ron, a neutered short-haired domestic, adopted us shortly after he was born into a feral colony. He and his litter-mates were days old when we realized they were disappearing: raccoons, hawks, and cars are the usual harbingers of death for street cats. With help from a local trap, neuter, and release program, we saved a few dozen felines who went on to live healthy lives in our neighborhood.

Ron, however, never ventured far beyond our front doorstep. When the weather turned unexpectedly cold, he slipped in and made himself at home. He was the first of three ferals who moved in with us.

Our only real concern prior to a semi-annual exam was that Ron was pooping outside the litter box. We had tried the usual solutions—another box, keeping the boxes scrupulously clean, treating stains with a deterrent—without positive results. Otherwise, his behavior was playful and affectionate. His appetite was good; we had consciously reduced his weight from a scale-tipping 18 pounds to 14.5 pounds.; and his special diet to prevent a recurrence of bladder stones was working. Regular pathology of blood and urine was unremarkable.

During the visit, however, our vet discovered a cyst on Ron’s right kidney while attempting to draw a urine sample. She referred us to Southpaws, a VCA specialty hospital where over the course of a few weeks, we consulted with an emergency doctor, internist, cardiologist, radiologist, and surgeon. The diagnosis: subcapsular perinephric pseudocyst.

Step One: Understand the Problem

Technically, Ron has a subcapsular perinephric pseudocyst, a fluid-filled sac sandwiched between the kidney’s lining and the organ itself. Although there is very little information about this condition available online and in print, I learned first that its specific cause is unknown, although it is related to kidney disease.

According to an internist at Southpaws, more than 30 percent of cats will develop kidney disease at some point in their lives. By the time they reach 15, more than half have some form of kidney disease.

Ron had none of the classic symptoms of kidney disease, like abdominal discomfort and vomiting. Routine blood and urine analyses had been unremarkable, except for one marker of early kidney disease. Sonograms showed that his kidney functions within low-normal ranges.

Before we could determine the best treatment option, the cyst needed to be drained and analyzed. Guided by state-of-the-art ultrasound technology that was developed for humans, the radiologist drained 180 milliliters of fluid (about three-quarters of a cup). A pathological analysis revealed no cancer, infection, or other abnormality. Based on Ron’s relatively healthy profile, the internist recommended surgery, but not without checking out another complication: a heart murmur.

An echocardiogram revealed that one part of the heart muscle had thickened, making it difficult for the organ to completely relax and fill with a sufficient amount of blood. The cardiologist concluded, however, that Ron would probably tolerate general anesthesia, although cats with structural cardiac disease have some risk for developing heart failure after surgery. She also determined that although Ron had slightly elevated blood pressure, he didn’t need medication.

We discussed all these finding with the internist and with Ron’s primary veterinarian. She was always available to discuss this rare condition with us. We wanted to do what is best for him—for his immediate health, his overall quality of life, and frankly, our budget. We had three treatment options for this relatively healthy cat: do nothing, surgical remove the cyst, or routinely aspirate it. Doing nothing was not option, so we met with a surgeon.

Step Two: Collect Data Points

The surgeon explained that he would use a cut-and-cauterize procedure to remove the cyst, but this would not eliminate the accumulation of fluid. To prevent fluid from simply pouring into the abdomen, he would resection the cyst wall to the abdominal wall with omentum, a fold of tissue membrane. Ron’s body would then assimilate and process the fluid.

The prognosis for this procedure is good if there is no underlying renal disease, and guarded if chronic kidney disease is present. Since Ron seems to have the beginnings of kidney disease, this was not an easy call. Furthermore, while the procedure sounded simple and would take less than an hour, the surgeon cautioned that it would be major abdominal surgery, requiring a long and closely monitored recovery. We would have to limit Ron’s activities and his playful interactions with Nina, our other cat. As with any surgery, there was risk of infection, complications from anesthesia, and emotional distress—to Ron, Nina, and us. Moreover, we understood that surgery was not a cure. It would only correct and manage the abnormality.

The surgeon then suggested we get at least another set of data points before we made our decision. In statistics, a data point is a single measurement. It is irrelevant unless and until it is compared to other points to determine a pattern. The fact that Ron had 180 milliliters of fluid was a single data point that meant nothing in and of itself. How long did it take for the fluid to collect? Was all of it aspirated? How long would it take to fill again?

Abdominocentesis, the ultrasound-guided aspiration of a cyst in the abdomen, has its own risks. “The shortest way to an abscess is through a cyst,” the surgeon had advised, meaning that each puncture carries with it the risk of infection. Also, because of continual fluid production, it provides only temporary relief.

We had the cyst drained again to begin to plot the pattern. The radiologist invited me to watch. Ron lay comfortably and unsedated in a V-shaped cushion as she drained more than 100 millimeters from a cyst the size of a flattened tangerine. She showed me his relatively healthy right kidney as well as the smaller left one, where a much smaller pseudocyst may also be forming.

We decided that draining the cyst every six to eight weeks would be our course of action. We could keep the cost down by not accompanying Ron to the procedure and not having the fluid analyzed. I had seen how relaxed he was and since we had already had the fluid analyzed, this was a welcome budgetary consideration.

After a third abdominocentesis, however, our radiologist had another concern: Ron had lost a full pound over a six-week period, even though he had a good appetite. She also noted a possible abnormality on his intestines, and suspected low-grade, small cell lymphoma. This type of cancer is not aggressive and is typically found in older cats, with males being slightly more predisposed than females. A definitive diagnosis would necessitate a biopsy, and based on its location, this would require abdominal surgery. We were back to that.

She recommended prednisolone. Our primary vet agreed. Beyond being palliative, the steroid regime would reduce inflammation and stimulate his appetite. Within days he began to eat like teenaged boy; in two months he gained back a pound.

Step Three: Chill Out

In the midst of the initial month-long series of exams, Ron became constipated, setting up another series of alarming calls and vet visits. In addition to having been poked and prodded by strangers, he now suffered the indignity of an enema. Days passed and he was still not normal.

We called Ron’s primary vet in a panic. Unlike the high-tech specialists at Southpaws, she is more of a country doctor with long gray hair, bright eyes, and expressive hands. She listened to us and then asked for a minute to review Ron’s reports. By now, they were numerous.

“Here’s what’s going on,” she finally said, “Ron’s whacked out. “

She was right. Although we had done a lot to socialize him Ron was from birth a feral. He never had abided vet visits—at best, he tolerates them.

“Give him a quarter teaspoon of Miralax. Get him to drink lots of fluids. Don’t bring him in. Try to establish a normal routine.”

It worked.

We were reminded that as a cat, Ron’s primary purpose is to bring us joy. He eats well, loves to play, cuddle, and even fight with Nina. He chases laser-point flies and prism rainbows like a kitten.

When we brought Ron home from his first abdominocentesis, he just stared at me. Perhaps he was saying, I don’t know what you just did, but I feel better. Or maybe, I don’t know what you just did, but don’t ever do it again. Or maybe he was telling me, as T.S. Elliot observed,

His mind in engaged in a rapt concentration

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name:

his ineffable effable

Effanineffable

Deep and inscrutable singular Name.

He was just being Ron.